Jails Are America’s Largest Mental Healthcare Providers

The severely mentally ill are often more likely to find themselves in jail — and receive poor treatment — than to get the right care in their community.

People with severe mental illness — such as psychosis, hallucinations, or delusions — often don’t recognize they are sick and don’t get or maintain treatment, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit organization that advocates for better laws and treatment for the severely mentally ill.

As a result, they are more vulnerable to harm and more likely to harm others. So, it’s no surprise that law enforcement is often involved in mental health crises.

The good news about mental health problems is that medical advances in medication and behavioral therapy have resulted in effective treatments for many forms of chronic mental illnesses. Unfortunately, there is bad news about treatment, too — access to help is too often lacking for many people who sorely need it.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Follow-up Care for Anxiety and Depression Treatment

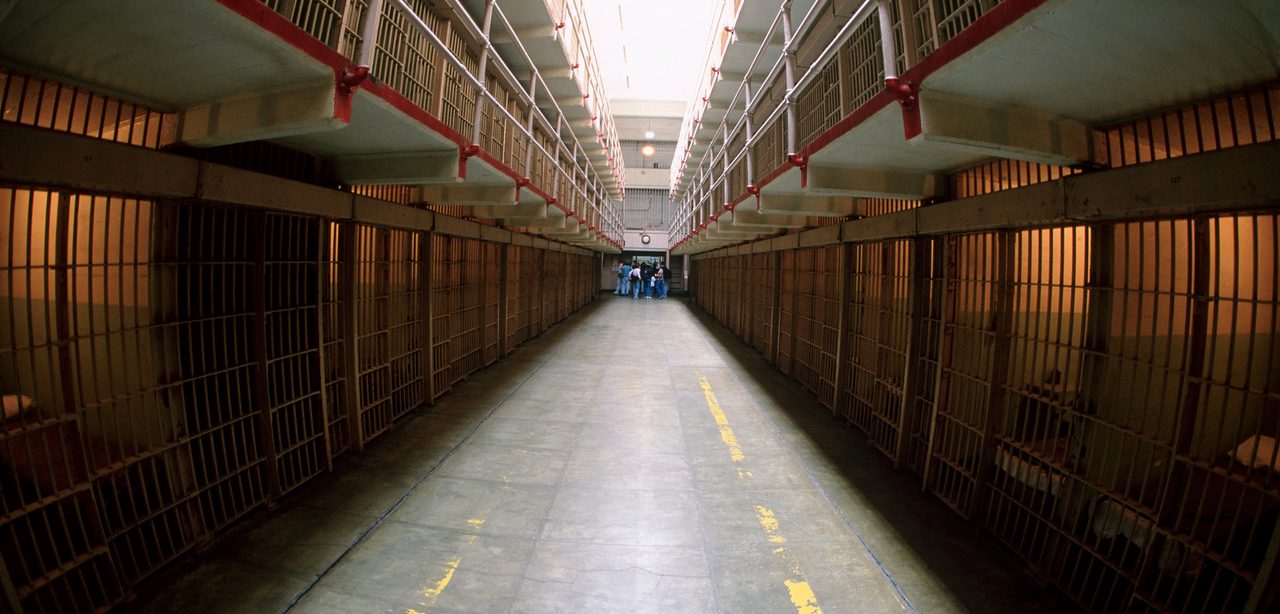

Funding for community mental health treatment has dropped in recent decades, and the severely mentally ill too often find themselves with no place to go. States across the country have closed psychiatric centers in recent decades, dramatically reducing available care. The result is that many mentally ill people are sent to prisons and jails instead of receiving psychiatric and psychological help, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Sending mentally ill people to prison, often without adequate treatment, can worsen their health and complicate their recovery because spending time in prison can create additional barriers to housing and employment when such people are released. It also places extra stress and burdens on law enforcement and correctional systems.

Law enforcement officers in most communities typically have few options. When leaving a person on the street will endanger themselves or others, they can take a person only to the emergency room or to jail.

Sending many mentally ill people to prison simply because there is no place left for them to go ends up costing taxpayers countless dollars, the Treatment Advocacy Center points out. In fact, the average cost for psychiatric treatment in a community hospital ranges from $3,616 to $8,509, depending on the type of mental illness being treated. If that kind of money is instead spent on incarcerating a mentally ill person for 35 to 83 days, a psychiatric hospitalization might produce a better chance of treatment and recovery, especially for juveniles.

Police can be put in a difficult position, trying to de-escalate encounters with severely ill people while having to do their law enforcement duties. In San Antonio, an award-winning, innovative program is helping law enforcement address these problems. Officers attend a 40-hour training program developed by Leon Evans, head of the city’s Center for Health Care Services, and learn the symptoms of mental illness and skills for dealing with, calming, and, when possible, helping the mentally ill in crisis get evaluated at a city crisis intervention center and diverted to treatment.

It’s a model being adopted elsewhere, one that saves $10 million a year while reducing jail populations. The hope is the success of the program may be a template for other police departments around the country.

“Something’s wrong when the majority of people with severe mental illnesses are in jail and not in treatment,” Evans said. “It costs taxpayers a lot of money. It’s better not to criminalize somebody in the first place. We don’t put people with diabetes in jail, so we shouldn’t be putting people with mental illness in jail.”

There is also potential good news about ways to help individuals with serious mental illness who are in prisons. In an analysis of 21 studies of interventions targeting people with serious mental illness in the criminal justice system, researchers from the University of Utah and the University of North Carolina found nine interventions that reduced the odds mentally ill people in prison would again end up in prison once they are released.

The most successful in-prison therapies incorporated some form of cognitive behavioral therapy or therapy for substance abuse disorders. The research showed those who participated in these programs in prison had shorter lengths of stay in jail compared to those who did not participate in a treatment program.

Updated:

November 22, 2022

Reviewed By:

Janet O’Dell, RN